One step ahead of the cancer

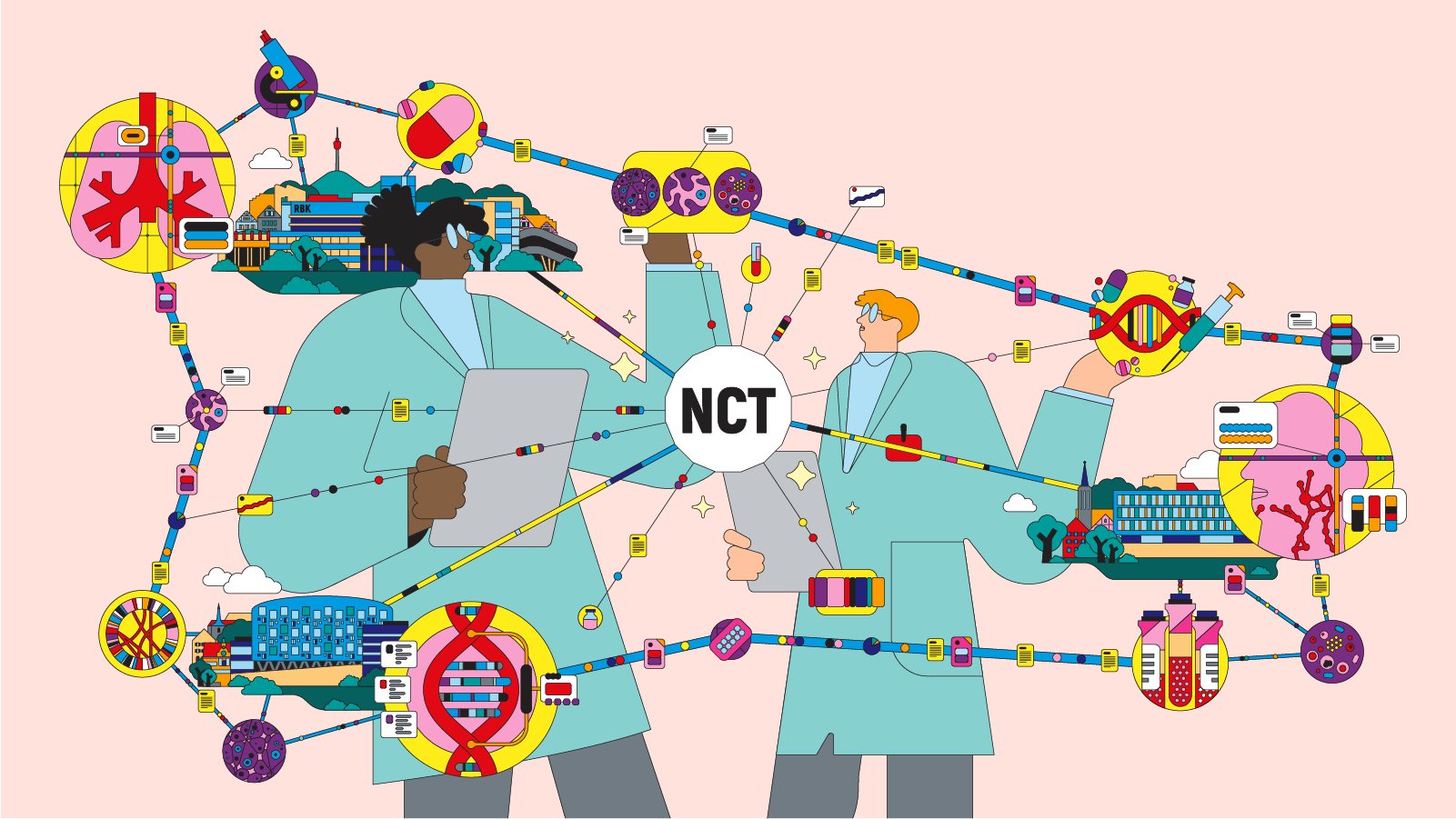

Starting in 2024, Stuttgart, Tübingen and Ulm will collaborate to establish the German National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) SouthWest. There, experts from the Bosch Health Campus in Stuttgart and the university hospitals in Tübingen and Ulm will work on customized cancer therapies. Patients are already benefiting from this exchange – for example, through the Molecular Tumor Board.

White LED ceiling lights, large whiteboards for jotting down ideas, filter coffee in thermos flasks: a conference room like millions of others. However, this seven-person meeting is not about sales figures or marketing strategies but about life and death. Every Thursday at noon, the Molecular Tumor Board – consisting of experts from the Robert Bosch Hospital in Stuttgart and the Tübingen University Hospital – meets to discuss cancer cases. An example: "Lung cancer, EGFR exon19 deletion, initial diagnosis 04/2018, since then targeted treatment with afatinib, followed by osimertinib. Currently renewed progression and resistance testing with detection of a T790M mutation and a C797S mutation, in trans." Everyone in the room is nodding their heads.

Five years ago, Maria Kamm (not real name), 72, was diagnosed with lung cancer, and her odds were not good. "Lung cancer is still very deadly," says Prof. Dr. Hans-Georg Kopp, chief physician at the Center for Tumor Diseases and head of Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Medicine at Stuttgart's Robert Bosch Hospital. "However, truly incredible progress has been made in researching that cancer over the past decade – especially at the genetic level." This is exactly what the work of the Molecular Tumor Board is all about. At one of the previous tumor conferences, Dr. Annette Staiger, a molecular biologist at Robert Bosch Hospital, and Dr. Christopher Schroeder, a human geneticist at Tübingen University Hospital, shared an important piece of information: Ms. Kamm's cancer has a mutation in the EGFR gene, which is responsible for the tumor’s growth. This opened up new possibilities for oncological treatment – and new prospects for Ms. Kamm.

The Bosch Health Campus brings together all of the Foundation's activities and institutions in the support area of health: the treatment of patients, biomedical research, medical and nursing education and training, and the funding of promising new ideas for better health care. Three institutions on the campus - the Robert Bosch Hospital, the Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch Institute for Clinical Pharmacology and the Robert Bosch Center for Tumor Diseases - will work together with experts from Tübingen and Ulm on the new NCT SüdWest.

Alliances in the battle against cancer

Tumor boards facilitate the interdisciplinary exchange of information on oncological cases and are now standard practice when it comes to diagnosing and treating cancer. The Molecular Tumor Board of the Bosch Health Campus and the Tübingen University Hospital is an exception nevertheless, because it brings together the latest research from both hospitals on genetics and oncology – benefitting patients like Ms. Kamm. This life-saving form of cooperation between and among different disciplines, faculties and hospitals will be placed on an even broader footing in the future: In the spring of 2023, a consortium of the Bosch Health Campus in Stuttgart and the University Hospitals of Tübingen and Ulm won the bid for the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) SouthWest.

As part of the "National Decade Against Cancer" launched by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, hospitals and research institutions throughout Germany were able to apply for the title and for funding. Stuttgart, Tübingen and Ulm prevailed and are now part of a nationwide excellence network that will receive funding of up to 98 million euros per year from both the federal and state governments. The NCT SouthWest will include a new 6,000+ square meter facility at the Tübingen site, the centerpiece of which will be an "Early Clinic Trials Unit." This will literally provide more space for one of the core competencies of the three institutions: research into new cancer therapies – and their rapid translation into everyday clinical practice. "The tumor center does not only seek to generate new knowledge," says Prof. Dr. Alscher, managing director of Bosch Health Campus GmbH Stuttgart and professor at the University of Tübingen. "Our goal is to enroll 20 percent of our patients in clinical trials in the next two years – twice as many as today."

The Robert Bosch Hospital specializes, among other things, in the treatment of lung cancer. At the Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch Institute for Clinical Pharmacology, research is carried out in the field of personalized medicine.

A new generation of drugs

The case of lung cancer patient Maria Kamm is an impressive example of how high-speed medicine can save lives. Until about ten years ago, the only treatment available for most lung cancers was cytostatics, commonly known as chemotherapy. However, these drugs inhibit cell growth not only in the tumor, but throughout the body – with the resulting side effects. A new generation of drugs – so-called inhibitors – targets the tumor's metabolism directly; for them to work, the tumor must have a corresponding mutation. And because the cancer is able to learn and develop resistance to the inhibitor, "a cat-and-mouse game ensues between the drug and the tumor," explains molecular biologist Dr. Annette Staiger. "We always need to be one step ahead."

In Ms. Kamm's case, the experts recognized that in addition to the disease-causing mutation, her cancer had two different resistance mutations – but distributed across two alleles. This means that a combination of two EGFR inhibitors, in tablet form, can be used in this patient. Dr. Annette Staiger says: "This way, we were able to use two different generations of EGFR inhibitors for treatment, which fail as individual substances but remain effective in combination. We thus outsmarted resistance." From the point of view of the attending physician, Prof. Kopp, this case is not only lucky for the patient, who can continue to be treated successfully with tablets; it is also a concrete outcome of current research into resistance: "We had to do a very detailed analysis of the genome of the tumor. That is still the exception, and we are rather proud of the fact that we, together with Tübingen, have the capacity and ability to perform this highly accurate work and then discuss it on the Tumor Board."

The Tübingen University Hospital has built large gene sequencing capacities, which help improve the identification of individual cancer drivers.

Doubling performance on a regular basis

Human geneticist Dr. Christopher Schroeder from the Tübingen University Hospital comes into play when large-scale genome analyses are needed. He then takes the tumor and blood samples with him and has them processed in Tübingen. When he talks about the equipment used to do this sequencing, he sounds a bit like a boy raving about the performance of his airplanes in a quartet card game. "With the 'next generation sequencing' we use, several hundred million DNA fragments in a sample can be examined in parallel," says Dr. Schroeder. Until a few years ago, Tübingen was able to study 300 genes in tumor and patient genomes. Then it was 700. As of the beginning of 2023, it is possible to analyze the entire exome, i.e., the "writing" part of the DNA: about 23,000 genes. "And it takes just a few days," says Dr. Schroeder. Everything suggests that the rate of increase in the capacity of genetic diagnostics exceeds even Moore's famous law, according to which the number of transistors on a chip doubles every 18 to 24 months. According to Dr. Schroeder, "we can only guess what will be possible in a few years."

In comparison, the exchange and collaboration within the Tumor Board seem almost unspectacular: seven people in white coats are sitting together, scrolling through charts and tables and throwing out phrases such as "EGFR C797S, both trans." But that's how it often is in research: true, effective innovation emerges when something special is translated into everyday life and becomes routine.

Ulm University Hospital focuses on blood and lymph node cancers.

The long game

On this particular day, the Tumor Board discusses twelve cases. Some of them are patients from overseas who have heard about the genetic expertise of the hospitals in Stuttgart and Tübingen and have registered for treatment. Bandying around acronyms and abbreviations, the experts discuss the possibilities and prospects of individual therapies. Sometimes the answer is a brief, resigned shake of the head before they quickly move on to the next case. "In most of the cases we discussed today, however, we had some good news," says Prof. Kopp after the session. "And Ms. Kamm's case is truly sensational: She's been diagnosed with cancer for more than five years – and she hasn't had to endure chemotherapy yet."

In 2019, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research launched the "National Decade Against Cancer" and "Vision Zero": the hope that in the future not a single person will have to die from cancer. "Unfortunately, we are not there yet," concedes RBK head Prof. Alscher. "But more and more often, cancer can be converted into a chronic, i.e., no longer acutely life-threatening disease, or even cured." The new NCT SouthWest will be a crucial site in this battle, with new infrastructure, new man and woman power, and new ideas. The interdisciplinary exchange among the best in the field will then not only take place every Thursday at noon but every day. Cancers will have to brace for an uncomfortable decade.